Dedicated Followers Of Kinks' London

From Waterloo to Muswell Hill, Ray Davies was the poet laureate of the capitalBy Richard Abbott

Here's a pop-quiz question:

As long as I gaze on Water-loo sunset, what am I in?

Yes, I am in paradise.

I'm in Waterloo now, sitting on the first floor balcony of the Reef Bar, with its commanding view down the sweeping concourse of Waterloo Station. So, if I were to tell you I was looking down at the millions of people, what would they be doing? That's right, they'd be swarming like flies round Waterloo Underground. Ray Davies, writer of Waterloo Sunset and leader of The Kinks, is the poet laureate of London, chronicling in his songs its glamour, its seediness, its pleasures, its follies, and its homely suburbs better than anyone before or since.

He wrote Dedicated Follower Of Fashion, which is about Carnaby Street, Lola about Soho, and Muswell Hillbillies about his home turf up on the hill. His song Victoria is, strictly, about the queen rather than the area, but you can stretch a point and add that in too.

In fact, so good is he at conjuring up the spirit of the capital city that you can take a Kinks Tour of London, starting at Waterloo, delving into the West End, heading north through Archway and ending up in Muswell Hill, singing his lyrics all the way.

Oddly, it's only called Waterloo Sunset rather than the original title Liverpool Sunset because the Beatles had just come out with their Liverpool-inspired Penny Lane and Strawberry Fields and Ray decided that, rather than seeming to follow in the Mersey's wake, he would transfer the location to his home city. I am very glad he did.

From my Waterloo vantage point I can do what is most interesting about rail-way stations - watch people. Pensioners getting lost, policemen in twos, pigeons in flocks and at any one time at least a dozen fond farewells and heartfelt hellos.

In Waterloo Sunset, Terry meets Julie every Friday night. Perhaps beneath the four faces of the station clock suspended, high above, from the glass roof. These days, Waterloo is not so much a station, more a shopping mall. I could do any number of things here, eat, drink, buy a shirt, send an e-mail , check out a Dali exhibition. There's even an impotence clinic.

Today, of course, the trains don't just go to suburban destinations carved into the war memorial arch - they leave for Paris, Brussels and Lille. But following the Kinks you walk north across Water-loo Bridge like Terry and Julie and feel safe and sound.

Ray Davies feels safe and sound in a little pub just across Waterloo Bridge in Savoy Street called the Savoy Tavern.

I walk there, against a north wind, overtaking foreign students bent double beneath their backpacks. The Journey's worth it. An unspoilt pub in the heart of London, plain bar, bare-board floor, cream-painted panel walls - the sort of place where Ray feels comfortable.

He mentions it in his book Waterloo Sunset, which is a curious blend of auto-biography, fiction and myth-making.

A girl is asked 'Who are you waiting for.' And she replies: The man who wrote Waterloo Sunset. I've been in the bar at the Savoy every night, just as he said, but he never comes. He's not ready to leave the underground.'

It sounds like whimsy, but its also a hint at the less-than-sunny side of Ray Davies. He is reputed, in 1973 when his marriage was breaking down, to have spent Christmas Day on the Circle Line, drinking cans of Kronenbourg.

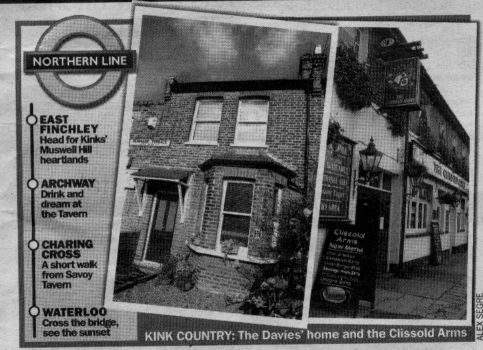

From the Savoy Tavern I walk along the Strand to Charing Cross and take the High Barnet branch of the Northern Line up to Archway station on the way to Muswell Hill.

The Archway Tavern had the distinction of appearing on the cover and inside the gatefold sleeve of the Muswell Hillbillies album. It's no longer the dark-wood and etched mirror place it was then, but somehow even more pertinent as a place to gaze into your beer and think, as Ray sang in Muswell Hillbillies, of coming from a nowhere kind of place but dream of place you've never seen -New Orleans, Oklahoma, Tennessee...

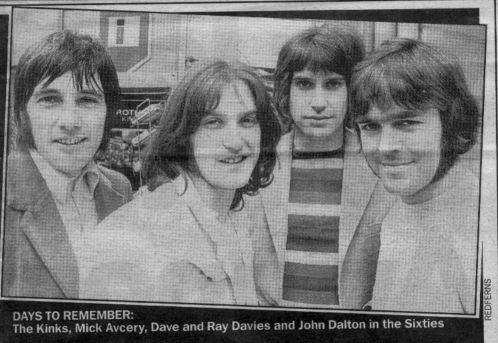

Then back on the Northern Line to East Finchley. From here, tree-lined Fortis Green takes me to Muswell Hill where Ray was born 56 years ago and grew up in 6 Denmark Terrace, just opposite the Clissold Arms.

The house, a Victorian semi attached to a joinery workshop, was cramped for a large family. It was a musical home, with a piano in the parlour, to which Ray's parents Annie and Frederick would weave back from the Clissold Arms with a gang in tow for a singsong. Here, in 1964, Ray and brother Dave worked out the chords to You Really Got Me, the song that first put them at the top of the charts.

The Clissold Arms is a real Kinks find. The large back bar has a display of Kinks memorabilia. Among them is a signed copy of the Kinks first single, a cover of Little Richard's Long Tall Sally, a guitar, a wall of photographs and a small brass plaque which reads: Site of 1957 performing debut of Ray and Dave Davies. Founding members of the Kinks.

Dave Davies' song Fortis Green goes: 'Mum would shout and scream when dad would come home drunk, When she'd ask him where he'd been, he said "Up the Clissold Arms", Chattin' up some hussy, but he didn't mean no harm.' If that sounds a bit of a rough pub be reassured it isn't. Actually it's an ideal place to stop for lunch (Tel: 02088831028).

On my way up Fortis Green I passed No.87, the home Ray bought when he was married to Rasa whom he'd met when she was still a Bradford schoolgirl and mad-keen Kinks fan. They had two daughter's and it's Rasa's falsetto that you hear on the backing vocals of Sunny Afternoon.

Ray and Dave went to school around here and went rock and rolling at the local hop. The Athenaeum, where Sainsbury's now stands, was the dance hail featured in the song Come Dancing. Athenaeum Place is still there like the inspiration for a Ray Davies vignette - a beggar on the corner, and cobbles leading to a former Victorian church that is now an O'Neill's 'Irish' bar.

I walk down Priory Road, high enough to see London at your feet, first the trees and terraces of the lesser houses in the valley, then the City's tower blocks and Wren churches, finally Canary Wharf, grey and blinking in the winter sunlight.

On Priory Road I find myself in another Kinks vignette as I reach the beer-sticky Northern Railway Tavern, step over a yawning dog in a tartan coat and pass a Baptist church with the sign reading 'Heaven Knows when You were last Here'.

I'm headed for the last outpost on my Kinks tour: their recording studios, Konk, on Tottenham Lane in Hornsey.

A blue neon sign spells out the name above the door. It's a windowless, beige-painted pebbledash place. Very anonymous, very North London rock star.

Such scenes are so evocative you could write a song about them.

Or at least, you could if you were Ray Davies.

For more information on all aspects of the Kinks, including locations log on to BigBlackSmoke.